|

by Kyle Schnoebelen

Don’t go to policy school. It is a hopelessly academic silo of idealism – brick-and-mortar manifestations of the outdated notion that “bigger government was better government.” People Who Actually Matter summarily ignore policy professors. And don’t even start on the students, who think themselves too good for local government, preferring to spend their days whining about social injustice and debating what it means to be a citizen of the world. At least, don’t go if you subscribe to the above view, recently presented in the Washington Post’s Outlook section by James Piereson of the Manhattan Institute’s Center for the American University and Naomi Schaefer Riley, a former blogger at the Chronicle of Higher Education. The pair present a depressing assessment of the state of public policy education, lamenting that policy schools are no longer useful because they aren’t “preparing their graduates to fix all that needs fixing.” They’re correct, in a sense. It would be surprising to find a school in any discipline that claims to endow graduates with the ability to “fix” every relevant issue in its field. If the authors expect this of policy grads, well, that goes a long way towards explaining their disappointment. Dismissing policy schools because graduates are not immediately capable of solving “all that needs fixing” is akin to calling medical schools useless because young MD’s have yet to cure pancreatic cancer or Alzheimer’s. No Kennedy School MPP has simultaneously made trash collection more efficient in Cambridge, eradicated poverty in Massachusetts, and protected U.S. intellectual property in China. So, game over. If waving a diploma at problems and hoping they go away isn’t working, the entire discipline must be useless.

0 Comments

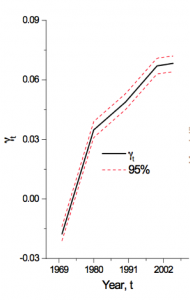

by Zach Porter There is often a time around mid-February where I find myself thinking two rather distinct thoughts. The first is generally selfish: “I sure do wish that there was someone special in my life that I could share Valentine’s Day with.” The second is entirely selfless: “I sure do wish that there was significantly less income inequality in America.” It may seem that these two thoughts are wholly disjointed, but that’s not entirely true. What if there was some way to guarantee both companionship for self, and greater equity for all? Such an outcome may be within sight. But who cares if more educated women are marrying more educated men? And how does marital sorting affect household income inequality?This is not a new question, and the authors cite several papers that have explored it before – each of which reach a similar conclusion: increasing assortative mating has increased household income inequality. In summarizing their findings, the authors highlight some income-to-mean-income ratios for different education pairings both in 1960 and 2005. Specifically, they find: “In 1960 if a woman with a less-than-high-school education married a similarly educated man their household income would be 77 percent of mean household income. If that same woman married a man with a college education then household income would be 124 percent of the mean.” While these combinations were likely selected to maximize income differentials, examining the income differentials of similarly educated households across time provides a more salient comparison. The less-than-high-school/less-than-high-school family in 1960 had an income equal to 77 percent of the mean income. by Lady Lockhart

The 1996 Welfare Reform Law replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. TANF implemented strict work requirements for welfare recipients, and since then, welfare caseloads have decreased by more than 50%. But are smaller caseloads an indicator of success? That depends. If the goal was to simply kick people off public assistance, then welfare reform has been successful. But if the goal is to help recipients and ensure their future success so that they don’t return to welfare, then no – welfare reform has been far from successful. From 1996 to 2000, the percentage of people “dependent” on welfare declined from 5.2 to 3 percent, according to a 2013 report from the Department of Health and Human Services. The “dependency” rate has since risen back to 4.6 percent, declining briefly only in 2006 and 2007. Millions of people cycle in and out of welfare, and a few common-sense changes could help improve the system. For example, the law should continue to provide supportive services, such as childcare, to recipients even after they have found employment. The current policy quickly renders recipients ineligible for childcare benefits when they find a job, creating a situation in which working mothers, unable to afford a babysitter and cut off from benefits, are forced to quickly exit the workforce. These mothers return to home and to welfare, perpetuating the cycle of dependence. Future welfare reform solutions need to be two-tiered. First, keep encouraging recipients to accept immediate employment while continuing to invest in their future marketability. Second, job training should be focused on retention and advancement so that recipients will have more sustainable employment. If welfare recipients accept seasonal or temporary employment, they should be coached on managing their finances accordingly, while also searching for full-time jobs. This leads me to my third point – financial literacy is key. Most welfare recipients are eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit, which comes in a lump-sum payment during income tax season. Many are also unemployed during this time, but could benefit from investing some of those funds for future expenses. Welfare policy needs to begin coaching welfare recipients on managing their finances in both good and bad times. by Graham Egan

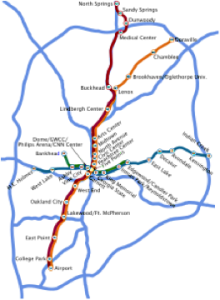

Nearly 50 years after the demise of Jim Crow laws, administration of justice in the United States is still far from color-blind. In some places, however, color matters more than others. In Texas, African Americans continue to be sentenced to death because of their race. The application of capital punishment in this manner makes a mockery of fundamental principles in the American criminal justice system: fairness and equality before the law. Duane Buck is the most recent recipient of unequal treatment at the hands of the Texas criminal justice system. In a 6-3 decision handed down on November 20, 2013, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied his appeal for a new sentencing hearing, despite clear evidence that racial bias contributed to his original death sentence. Mr. Buck, an African American in his fifties, was convicted in 1997 of two murders in Harris County, Texas. Although his guilt in these gruesome crimes is undeniable—Mr. Buck does not deny that he committed the murders—the tactics utilized by prosecutors to pursue a death sentence were overtly racist. The Harris County prosecutors elicited testimony from Walter Quijano, a psychologist, who affirmed that the “race factor, black, increases the future dangerousness for various complicated reasons.” Because a finding of “future dangerousness” is a prerequisite for a death sentence in Texas, the prosecutor relied on Dr. Quijano’s testimony to convince the jury to sentence Mr. Buck to die.  Current MARTA transportation routes. Current MARTA transportation routes. by Sarah Collier Atlanta’s primary public transportation system, the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA), has recently released plans to expand their railway transit lines to the North Fulton in the Georgia 400 corridor, an area with a growing job market. While this expansion provides those north of Atlanta easier access to a Jamba Juice, it also represents a significant first step towards decreasing the racial inequality perpetuated by MARTA’s current railway transit routes. Having worked for two summers in Atlanta, my most prominent memory was the long commute between the white suburbs north of Atlanta, where jobs are plentiful, to its impoverished black neighborhoods downtown. I would have used public transportation, however the MARTA suspiciously ends right before white suburbia begins. MARTA’s transit route design is sorely lacking. With its simple cross-shaped track, it has a local reputation as only being useful for getting to either a Brave’s baseball game or the airport. My long drives to work gave me ample time to wonder if it was simply unskilled urban planning or some other factor that had caused MARTA’s limited route design. As it turns out, MARTA’s history reveals racial discrimination as a key player in this debacle. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2022

|

ADDRESSVirginia Policy Review

235 McCormick Rd. Charlottesville, VA 22904 |

|

|