|

President Biden holds the upper hand in negotiations but still needs to get to the negotiating table

Speaking before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on March 10th, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that it is up to Iran to make the first move when it comes to nuclear deal talks. In his testimony, he made it clear that the Biden administration would offer no sanction relief until Iran restores full compliance or enters a “negotiated path toward full compliance.” The problem is, Iran has signaled a similar hardline stance: no sanction relief, no negotiations. “The answer is that the one who has left the JCPOA [Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action] has to come back first,” said Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s nuclear chief, to PBS on March 9th. Mr. Blinken acknowledged the challenges of re-entering the deal the U.S. pulled out of three years ago, saying that it will not be as simple as “flipping a switch.” This impasse will certainly be difficult to overcome. With both countries remaining unyielding - and seeking significantly different outcomes of hypothetical negotiations - there is plenty of reason to doubt that a new deal will be reached anytime soon. But, the Biden administration has reasons for optimism. The Iranian economy is hurting and some say the balance of power has shifted towards the U.S. By leveraging the impact of the sanctions, and the interests of allies in the region, Mr. Biden should be able to renegotiate a nuclear deal that fulfills a key campaign promise and accomplishes goals beyond the scope of the original agreement.

0 Comments

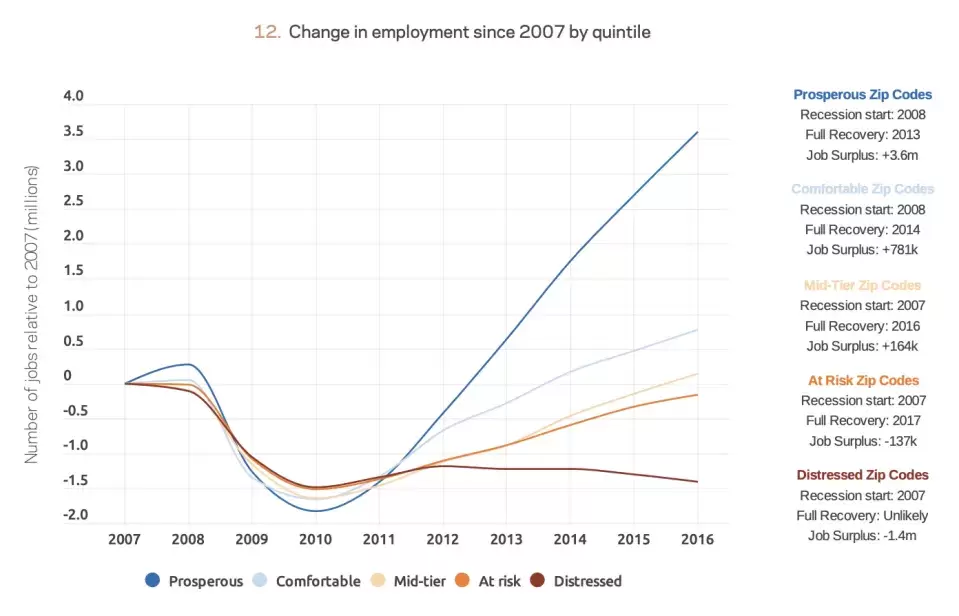

With the end of the pandemic in sight, many are hopeful for a swift economic recovery. But as the exact timing of a return to normal remains uncertain, so too does the fate of millions still looking for work and wondering if homelessness is just around the corner. In an attempt to extend a lifeline, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan. This $1.9 trillion dollar measure not only provides another round of stimulus checks, but also extends unemployment benefits, doles out aid to families with children, assists state and local governments, and bolsters pandemic response efforts. Many cheered the Act’s passage, but it turns out that neither politics nor economics admit of happily-ever-afters. And so the story continues, featuring a small but growing chorus of economists warning that excessive stimulus risks “overheating” the economy and causing difficult-to-manage inflation. Given the Rescue Plan’s party-line backing, it might be tempting to brush these claims aside as political attacks. Yet the inflation hawks are not so ill-intentioned. Not only are they bipartisan, led in part by former Obama official Larry Summers, but they are also correct in pointing out that inflation can have potentially dire consequences. In the 1970s, for example, “The Great Inflation” severely eroded consumers’ purchasing power and led the Federal Reserve to force a recession. While few might see a return of that era on the horizon, it nonetheless illustrates why we ought to take inflation seriously. This article is an attempt to do so, and to provide a balanced assessment of the future. Take a moment to reflect on the pre-2020 American economy: half a century of low unemployment rates, median income growth of almost 1% from 2017 to 2018, and 2-3% GDP growth during the four years preceding 2020. The headlines signaled the strength of the American macroeconomy. For all intents and purposes, the economy was booming. When we take a deeper look at the pre-2020 economy, we see a different story. While the headlines noted the low unemployment statistics and indicated continual monthly job additions, the reality playing out across the country was much grimmer. Since the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009, the top 20% of zip-codes--determined by labor, education, and housing statistics—across the country managed to fully recover from the recession in 2013. However, the 16% of American citizens who live in distressed zip-code communities still feel the recession’s devastating impact, as shown in the graph below. Mentioned in this publication previously, we should be paying more attention to the deterioration of the American community—whether that be weakening interpersonal ties or poverty.

A transition toward more efficient energy infrastructure serves as a focal point for combatting human-induced climate change. However, this transition raises questions regarding the current state of energy access across the United States and the nation’s ability to implement equitable energy transition policy for all.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) defines energy burden as “the percentage of gross household income spent on energy costs.” “Energy costs” consist of payments for powering amenities, like lighting, heating, and air conditioning, that require any sort of energy input — often in the form of electricity and natural gas. Unfortunately, paying to access energy supplies is a challenge for many households. According to a recent report released in 2020 by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), low-income households face a median energy burden of 8.1% nationally, over three times higher than the non-low-income household median burden of 2.3%. Such a burden is an increase from ACEEE’s previous report from 2016 detailing a median low-income burden of 7.2%. In its purest form, higher education is meant to expand upon and improve a vast array of student outcomes, from personal economic stability to health care access, critical thinking skills to self-esteem. It opens the door to a world of possibility, where collaboration and curiosity thrive. Despite these positive aspects, colleges and universities are more prone to flaws than not. They are business ventures which sell you on the promise of success, but only if you can pay to fit their mold of the ideal applicant.

From 1980 to 2005, four-year college tuition and fee expenditures rose from 40 percent of family income to 72 percent of family income for families in the lowest income quartile (McMahon, 57). A central flaw of higher education is the wealth and socioeconomic inequality of college and university admissions, which impedes access to these institutions. The costs of attending college are high, and they do not begin with the acceptance deposit. To be considered a strong applicant at most state colleges and universities, a student needs a wide range of extracurriculars and honors on their resume, many of which take significant time and money. Students from high-income families have a strong advantage when it comes to improving their chance of admissions. These families are able to afford private college tutors and counselors to oversee applications and edit personal statements and essays. School tours and visits, which may require hotel stays and airfare, are “of considerable importance” for 16 percent of public colleges. Connections and legacy status are considered in six percent of public college and university applications, including at the University of Virginia. For a base fee of $95, students can further impress admissions offices with Advanced Placement exam scores. While these advantages often lead to favorable outcomes for those who can afford them, they are not required by college admissions boards. Standardized tests, however, are. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2022

|

ADDRESSVirginia Policy Review

235 McCormick Rd. Charlottesville, VA 22904 |

|

|