|

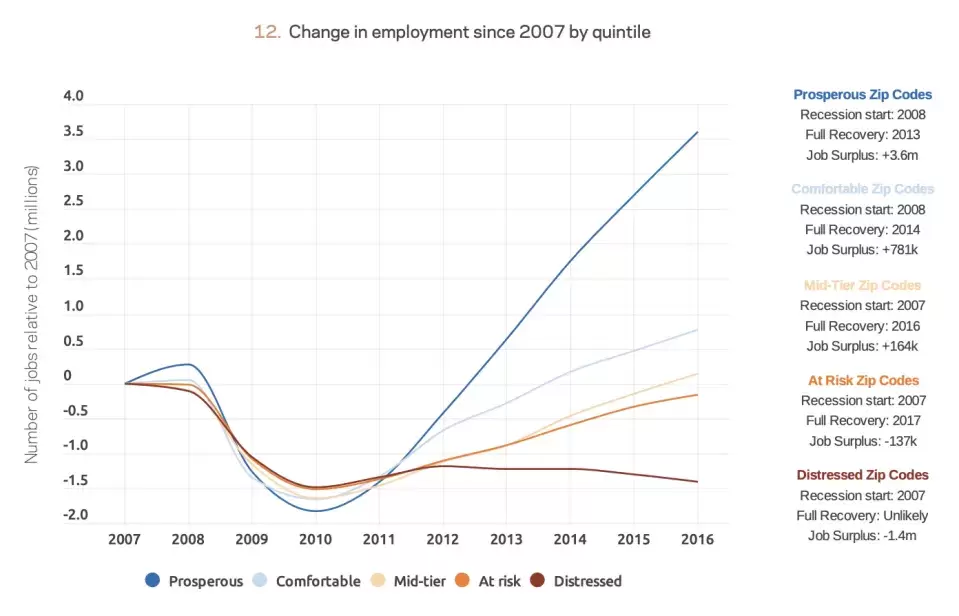

Take a moment to reflect on the pre-2020 American economy: half a century of low unemployment rates, median income growth of almost 1% from 2017 to 2018, and 2-3% GDP growth during the four years preceding 2020. The headlines signaled the strength of the American macroeconomy. For all intents and purposes, the economy was booming. When we take a deeper look at the pre-2020 economy, we see a different story. While the headlines noted the low unemployment statistics and indicated continual monthly job additions, the reality playing out across the country was much grimmer. Since the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009, the top 20% of zip-codes--determined by labor, education, and housing statistics—across the country managed to fully recover from the recession in 2013. However, the 16% of American citizens who live in distressed zip-code communities still feel the recession’s devastating impact, as shown in the graph below. Mentioned in this publication previously, we should be paying more attention to the deterioration of the American community—whether that be weakening interpersonal ties or poverty. How Did We Get Here? As the American economy began to diversify throughout the 1980s from manufacturing might to technological innovation, cities like San Francisco and New York pioneered the country’s shift to an innovative economy. With new opportunities in coastal cities, college graduates began to move to the coasts. This is commonly referred to as “the brain drain.” As large metro areas—referred to as “superstar” cities—continue to attract the country's brightest workers, they also attract the most innovative companies. From 2005 to 2017, five superstar cities contributed to over 90% of the growth in the United States’ innovation-sector. As these top cities grew, the lower 90% of cities suffered losses in the same sector. These losses expand beyond innovation: the “brain drain” ensures that individuals will flock to where innovation opportunities are ripe, leaving their homes. Despite its benefits, the innovation economy has uprooted the American community and is contributing to its demise. As regional divergence continues, it is only reinforced by venture capital firms. When we think of venture capital, it is difficult to not think of Silicon Valley and the booming tech hub that has spawned on the West Coast. Unsurprisingly, about 75% of the venture capital spending goes to three states: New York, Massachusetts, and California. COVID-19’s Affect on Distressed Cities But how has COVID-19 impacted smaller, distressed cities? Arguably one of the more interesting trends from the pandemic is that of Americans evacuating densely populated superstar cities and relocating to smaller metros. According to a Pew Research survey, about 20% of Americans moved as a result of the pandemic. For example, only about 18,000 workers left New York City in 2019, compared to the more than 110,000 that moved in 2020. That is a 487% increase. The rise of remote work during the pandemic has facilitated the migration from large metro areas to smaller cities. Remote work has contributed to an unwelcome loss of normality for many Americans. But people have become more productive, so much so that Stanford Economist Nick Bloom suggests that remote work will increase productivity in the U.S. by 2.5%. As workers move out of superstar cities, smaller metros are ready to accommodate. If remote work continues, cities like Boise, Idaho, or Bozeman, Montana, can attract more individuals than ever before. Before the pandemic, smaller cities looked to attract big business or promising talents with large tax incentives, grants, and zoning privileges. This became apparent when Amazon indicated it was looking for a new location for a second headquarters. The competition for “HQ2” resulted in over 200 cities across North America pitching their city as the ideal landing spot for Amazon. Luring Amazon to a small metro could have been monumental for economic development. Austin, TX attracted Apple and Tesla to set up shop in the up-and-coming city, catapulting growth and resulting in almost 22,000 new jobs during 2020. Yet, when Amazon chose Long Island City, NY and Arlington, VA—two areas of the country that are already prominent metro hubs—the prospect of transforming communities that have long needed a boost went unfulfilled. Now that the pandemic is encouraging a migration to smaller cities, these metros can focus resources on better schools, public services like parks and green areas, and safer streets instead of courting large companies. But this shift towards remote work means that new residential areas—apartment buildings, housing projects, and condominiums—must accommodate remote employees. This will require more home office space within buildings, not to mention the need for faster internet service in more remote areas. While remote work sheds a light on how resilient the American labor force can be, let’s remember that remote work particularly benefits those in skilled professions. The problems facing distressed metro areas cannot be solved with more remote workers moving to the community. A key question that needs addressing is how we can make the economy work for all. Growth for All of America Despite the thriving stock market—which reached historic levels in recent weeks—much of the wealth created has typically not led to reinvestment within distressed communities. However, in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Opportunity Zones, a provision which incentivizes businesses to invest in low-income cities and communities, have raised about $75 billion in capital between their introduction and 2019. (See all Opportunity Zone projects here). This legislation evidences the potential of targeted tax cuts for impoverished areas. According to an August 2020 report from the Council of Economic Advisors, Opportunity Zones have led to roughly a 1% increase in housing valuation within the communities, and such valuation will lead to $11 billion in new wealth. The report, however, mentioned that the coronavirus pandemic stunted Opportunity Zone investment within the second quarter of 2020. Nonetheless, the report signals that Opportunity Zones, with the COVID stimulus bills, will spur new investment within these communities across the country. While a promising start, Jonathan Gruber, an MIT Economist, expects more. In his 2019 book, Jump-Starting America: How Breakthrough Science Can Revive Economic Growth and the American Dream, Gruber suggests that to find the key to combating economic agglomeration, we must look at the past. During the decades after World War II, the United States invested heavily in public research and development (R&D). Funding reached its peak in 1964, when America spent 2% of GDP on research and development. Within this time period, the United States led the world in innovation, with breakthrough scientific feats like atomic energy, digital computers, jet engines, microelectronics, and satellites, not to mention putting a man on the moon. As of 2019, however, federal R&D spending accounted for roughly 0.7% of the nation’s GDP. Adjusting for inflation, this reduction in R&D spending is about $250 billion less annually than post-World War II spending. Gruber suggests we need to revamp our public funding for R&D. Gruber identified more than 100 smaller metro areas across the country that are potential new tech hubs just waiting to be jump-started. All of these areas, like Rochester and Syracuse, NY (both #1 and #3 respectively on the list) have young populations, prominent research institutions, and low cost of living. Gruber argues that government-run, place-based programs are better suited for ameliorating the ills of agglomeration in our current geographic job landscape. Adding to that, similarly to Opportunity Zones, a government-sponsored program would help combat income and opportunity disparities more than the private sector left to its own devices. Ideally, these programs would be set up via a non-partisan commission that identifies cities across the United States using comprehensive economic data. This process would avoid the political hassle of members of Congress fighting to get funding for cities within their own districts. After identifying metros, a rigorous peer-review system would be necessary to ensure that funds are properly spent. However, this involves patience—something the American political system is devoid of. Unfortunately, the political feasibility of this initiative is rather low given the debt implications of increased R&D funding. Our best hope is the continuation, or even expansion, of Opportunity Zones. Hope for economic development in smaller metro areas was given in recent weeks when the Biden Administration pushed for a comprehensive infrastructure plan. Such a plan could include funds to small metros specifically to revamp local economies. Yet, the merits of this plan continue to be subject to the willingness of Congress to significantly add to the federal deficit. Where We Go From Here As the United States recovers from the coronavirus pandemic, it is essential that we work to provide small metros with the same opportunities to grow as superstar cities. Hopefully, with the darkest days of the pandemic behind us, we can look towards a bright future for small metros; a future where we generate new tech and innovation hubs around the country, instead of reinforcing the old; a future where we find a way for the American economy to work for all, not just for those who live in superstar cities. What lies in front of us is an incredible opportunity to rebuild pockets of our country that have long called for our help. In the meantime, I ask for you to remain grounded within your communities and recognize the devastation that the pandemic has caused to our localities; support locally owned businesses; support minority owned businesses. This problem extends beyond political differences and our leaders need to step up to the challenge.

The views expressed above are solely the author's and are not endorsed by the Virginia Policy Review, The Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, or the University of Virginia. Although this organization has members who are University of Virginia students and may have University employees associated or engaged in its activities and affairs, the organization is not a part of or an agency of the University. It is a separate and independent organization which is responsible for and manages its own activities and affairs. The University does not direct, supervise or control the organization and is not responsible for the organization’s contracts, acts, or omissions.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2022

|

ADDRESSVirginia Policy Review

235 McCormick Rd. Charlottesville, VA 22904 |

|

SOCIAL MEDIA |